Pippa, age nine, has skipped three grades and achieved the goals of primary school.

Every Wednesday, she leaves her regular school for a couple hours to take an accelerated math class. Six children ages nine to 12 from several local schools work together in an escape room. They need to apply the intermediate algebra they have learned to solve the problems. Next week, they will participate in a math Olympiad for middle school students in Belgium.

Next-door, six primary school children are working on ‘physics for superheroes’. Do heroes in cartoons respect the laws of physics? And what if they did? In another class, students are reading a book in Latin, which gradually becomes more difficult and from which they derive the vocabulary and grammar of this ancient language.

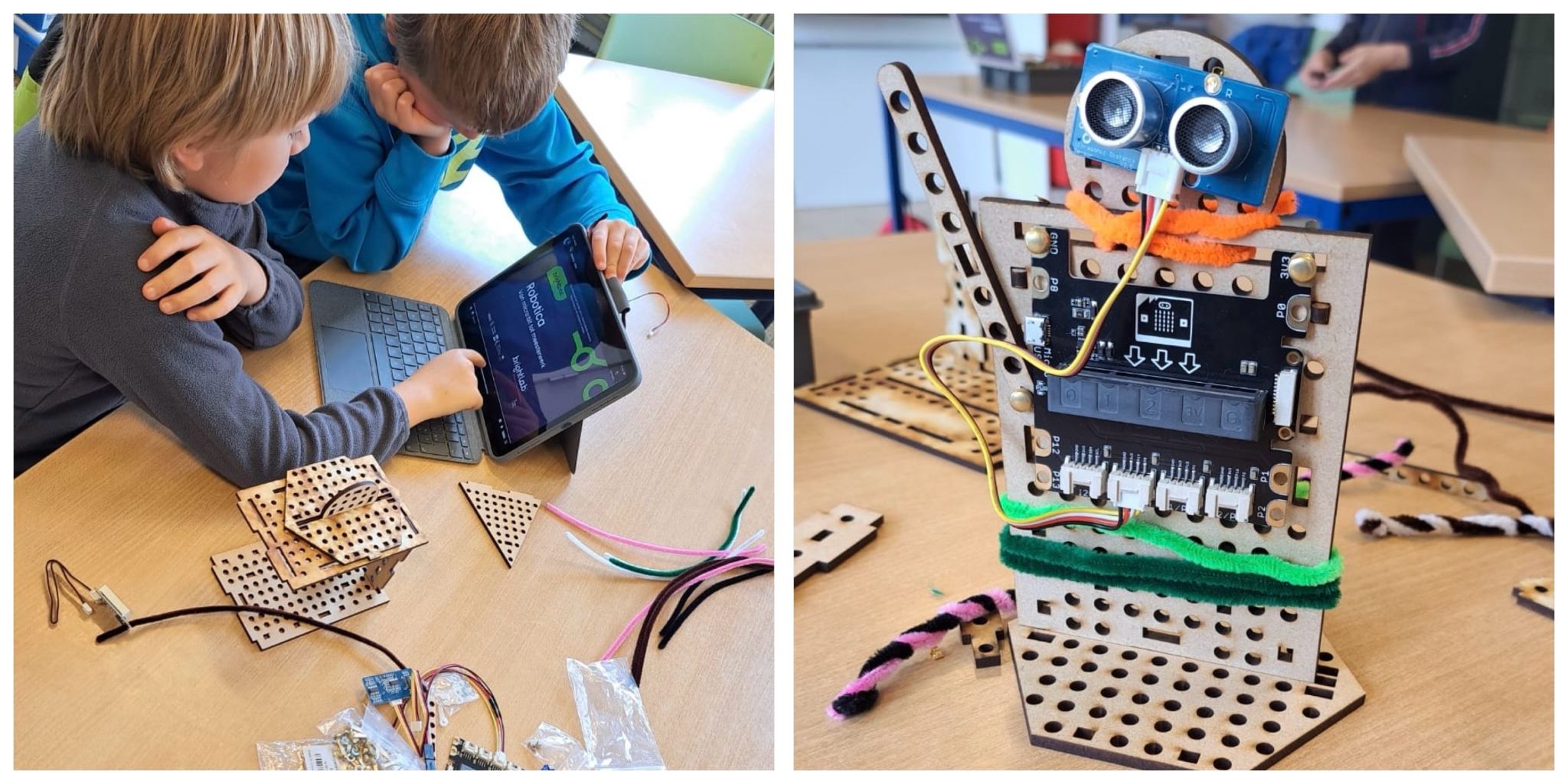

Scenes like this play out every day at Spring-Stof, a nonprofit co-founded by Kim that focuses on bright students in Belgium. But this model – bringing students to a central location for small group instruction with tailored, advanced curricula – is difficult to replicate in larger, lower-income, or less densely populated countries.

However, there are ways to bring elements of this educational experience to students almost anywhere.

First, a bit of perspective: as part of their mission to help every student succeed, schools often focus – rightly – on helping students who struggle to keep up with course material. But particularly bright students also have distinct needs. They often sit in classrooms where the pace is too slow and the material too basic. Without appropriate challenge, these students can become disengaged, frustrated, or even underperform.

Even if particularly bright students are satisfied with their environment, not challenging them is a missed opportunity to let them flourish and realize their potential. Patrick’s research shows that individuals who were exceptional problem solvers in their teenage years are especially capable of advancing the knowledge frontier (1). Ensuring particularly bright students learn better and faster allows them to contribute to innovation sooner. We need them to help find solutions to issues from climate change and the energy transition, to broader social and economic challenges. For instance, leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King and Steve Jobs skipped grades, allowing them to enter their careers without delay.

A complex case is that of twice-exceptional students – those who are both highly talented and have a learning difference or disability. Think of a student who excels in math and also has ADHD. While there is a tendency to focus support on such students in areas where they struggle, engaging her talent can be just as important, helping that student build the confidence to overcome the obstacles she faces [6].

Grade acceleration is a simple, low-cost way to help exceptionally bright students access the level of challenge they need to thrive. It allows them to progress through material at a pace that matches their abilities, preventing boredom and disengagement. Beyond individual benefits, acceleration can help society by enabling talented students to reach their full potential.

Do you know a student who may be ready to move ahead? Check out the IOWA Acceleration Scale, a tool that can help parents, teachers, and administrators determine whether a student could benefit from accelerated learning.

References

[1] Agarwal, R., Gaule, P (2020). Invisible Geniuses: Could the Knowledge Frontier Advance Faster? American Economic Review: Insights, 2(4): 409-24

[2] Bleske-Rechek A, Lubinski D, & Benbow CP (2004). Meeting the educational needs of special populations: Advanced Placement’s role in developing exceptional human capital. Psychological Science, 15: 217–224.

[3] Bernstein, B. O., Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2020). Academic acceleration in gifted youth and fruitless concerns regarding psychological well-being: A 35-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(4), 830–845.

[4] Steenbergen-Hu, S., & Moon, S. M. (2011). The effects of acceleration on high-ability learners: A meta-analysis. Gifted Child Quarterly, 55(1), 39–53.

[5] Schuur, J., van Weerdenburg, M., Hoogeveen, L., & Kroesbergen, E. H. (2020). Social–emotional characteristics and adjustment of accelerated university students: A systematic review. Gifted Child Quarterly, 64(2), 1–23.

[6] Raising Twice-Exceptional Children, Emily Kircher-Morris